Response to Road Safety Inquiry lacks urgency

1 Apr 2025

Earlier this month the Victorian Government released its long-awaited response to the 2023-2024 Parliamentary Inquiry into the Impact of Road Safety Behaviours on Vulnerable Road Users.

The government’s response indicates the extent to which it does or does not support 56 high-level recommendations tabled by a parliamentary committee in May 2024. The inquiry’s committee was made up of seven lower house MPs (4 ALP, 2 Liberals, 1 National Party).

Victoria’s road safety inquiry was sparked by the growing number of deaths and injuries to vulnerable road users (people who travel outside of vehicles, such as by walking or cycling).

Over 300 organisations and individuals made submissions to the inquiry, including Victoria Walks.

Why was the inquiry called?

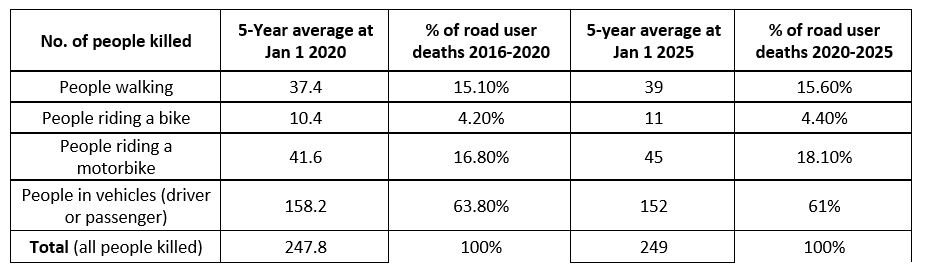

Victoria’s 10-year road safety strategy aims to halve all road deaths by 2030 (on 2020 levels). We’re at the four-year point of the decade, but the government is actually performing worse for all road users except vehicle occupants (see table above).

Worryingly more walkers are being killed now (in raw numbers and as a percentage of all road fatalities) than were being killed at the start of the decade.

In 2020 an average of 37.4 walkers had been killed in Victoria in each of the previous five years. In 2025 this figure has risen to 39. This year is already off to a horrifying start with 11 walkers killed by the end of March compared to the 5-year average of seven.

The proportion of people killed on Victoria's roads who are vulnerable road users has gone from 36.2% to 39% over this period (five-year average). Victoria Walks has also highlighted that the proportion of older adult walkers killed (as a proportion of all people killed on the roads) has been steadily increasing.

If the Victorian Government has any serious intention of achieving its 2030 target (or even making inroads) it will need to get its skates on and do things very differently.

So where to from here?

What changes did the parliamentary committee call for?

The parliamentary committee’s 56 recommendations to the state government covered a range of road safety levers including changes to Victoria’s road safety and transport strategies, road rules, speed limits, road safety infrastructure, road safety spending and road user education.

Some of the recommendations to government picked up on Victoria Walks’ 2023 submission and it is great to see the government response supported many of these proposals (some fully, some in part, and some in principle).

On vehicle speeds (recommendations #5 and #6)

Victoria Walks was not alone in calling for urgent changes to allow road managers to implement safer speed limits in areas where lots of vulnerable road users mix with people driving vehicles.

The government supported (in principle) the parliamentary committee’s recommendations that the Department of Transport and Planning (DTP) revise speed limit policy and technical guidelines to usher in safer speeds, noting a committee finding that it should be easier for councils to create 30km/h zones near schools (for example) as well as make other changes from the usual speed limit of 50kmh.

The government said it would continue to ‘explore ways to reduce red tape’ but also indicates it is waiting for the results of current trials of 30km/h zones occurring in some council areas around the state to make substantive changes to the speed zoning policy. This is disappointing given the link between speed and road trauma is already clear, with the government’s own road safety partners among those making submissions calling for safer speeds.

The government pointed out that the most recent updates to the Speed Zoning Technical Guidelines had allowed councils to apply 40km/h speeds to local areas. Activity centres must still be at least 400m long to be eligible for 40km/h under the guidelines.

Separately, the government indicated full support for a recommendation to work with councils to improve traffic calming in school precincts. However it did not foreshadow any new initiatives other than a program to provide Prep and Year 7 students with information on safe active travel routes.

On road design and road safety strategy

Victoria Walks’ submission to the inquiry called for a pedestrian-specific road safety action plan to address common pedestrian crash scenarios. Disappointingly, the parliamentary committee did not take up this recommendation, instead calling broadly for ‘greater emphasis on the safety of vulnerable road users in future road and urban infrastructure design and strategies’ (recommendation #8).

In response the government pointed to DTP’s 2024 Road and Roadside Safety Policy (see p.27 of this link), which outlines DTP's alignment to the Safe System philosophy, for example, by designing new roads in ways that separate vulnerable road users from vehicles. The new policy includes requirements that new and upgraded signalised intersections must not allow filtered right turns across vehicles and pedestrians (red and green arrows will be used) and that pedestrian head starts must be provided at left-turns.

This is something we have been calling for since our 2016 report Safer Road Design for Older Pedestrians. However the policy only applies to new state-managed arterial roads, or to major upgrades on arterial roads.

There is no clear commitment to invest in retrofitting the many existing streets where crashes are occuring. Communities will have to wait until their pedestrian black spots are assessed as most worthy of upgrade.

The government said DTP will work with local councils to encourage adoption of its Roadside Safety Policy approach on local roads.

Victoria’s Walks’ submission to this inquiry also called for changes to design standards, ‘particularly at crossing points and intersections to improve pedestrian safety and priority’.

The government response to recommendation #8 also pointed to DTP’s Movement and Place framework, the strategic tool this government has used to guide street management to ‘balance and optimise the different roles that roads and streets play in a city …’ It points out that the ‘entire metropolitan road network has been classified using the Movement and Place framework’.

We feel a shortcoming of Movement and Place is that it typically categorises walkers under its ‘Place’ function, meaning street managers consider people walking in places like town centres, but may not have to prioritise walking to places, especially crossing major roads.

However, the government did indicate ‘in-principle support’ for adopting a Road User Hierarchy (recommendation #1). Depending how and if this is applied, a road user hierarchy that puts walkers at the top of the priority pyramid could usher in genuine and wide-ranging improvements for walkers across Victoria’s road network.

The government response says DTP will work with its road safety partners to investigate this approach for ‘a Victorian context’, and noted the committee’s finding about the UK Highway Code (2022), which ‘prioritises and guides road users based on their level of vulnerability in traffic’.

On active transport policy

The current government has recently dropped development of a Walkable Communities Strategy, pivoting instead to an umbrella ‘Active Transport’ strategy. This new strategy will seek to encourage more walking and cycling but also encompass micro mobility such as e-scooters.

We feel there is a real risk this forthcoming Active Transport strategy will dilute planning and funding streams specific to walking and instead focus on multi-purpose infrastructure such as shared paths. Shared paths can actually discourage walking among older adult walkers.

On public transport

In its response to the parliamentary committee’s report, the government has supported ‘in full’ a recommendation to ‘continue to invest in public transport to make it a more attractive option’.

In its response the government pointed to its existing public transport plans and major projects (such as the Suburban Rail Loop and level crossing removals).

Importantly though the government response acknowledges that ‘modal shift from private vehicles to public transport helps create safer environments for vulnerable road users.’

On a very basic level this is an overdue concession that planning and policies that facilitate or force private car ownership also facilitate road trauma. Victoria Walks’ road safety submissions have called for the state government to ‘invest in modal shift from driving to walking, cycling and using public transport to improve safety of vulnerable road users’.

In addition to investment in public transport the committee recommended that public transport stops and interchanges be incorporated into planning to allow more people to safely walk or ride to public transport.

It was great to see in its response to this that the government has picked up on an earlier Victoria Walks’ advocacy position to install more pedestrian crossings near bus stops. The government said DTP is ‘reviewing design guidelines for bus stops to ensure safe pedestrian crossings are included in new bus stops plans.’

However, a Victoria Walks recommendation to ‘invest in walking to train stations, with $100m over four years to improve walking routes within 800 metres of train stations’ was not adopted by the committee (or government).

On overall investment in active transport

Frustratingly the government has not supported a recommendation by the parliamentary committee to make active transport funding levels more transparent by ‘reporting the proportion of the transport budget allocated to active transport’.

The Climate Council estimated active transport funding at 2% in a story in The Age just prior to the 2022 Victorian election. The United Nations recommends that 20% of transport budgets be directed towards non-motorised modes.

Victoria Walks has previously called for $600 million over the current government term to build pedestrian crossings, footpaths and better lighting on routes to schools and shops. Our 2025-2026 Victorian budget ask is for $250m to improve local recreational walks and $100m to install crossing and fix other missing links.

On funding for pedestrian projects

The government supported (in part) the parliamentary committee’s recommendation (#27) that DTP review the number of pedestrian crossings on arterial roads linked to public transport stops, activity centres and schools.

But while it has committed to planning for pedestrian crossings linked to new bus stops it does not appear committed to further specific investment in crossings (outside of current funding streams) at this stage, rather saying DTP is developing ‘a new pedestrian risk rating and forecasting tool… to identify areas of high pedestrian risk to inform state and local government planning and future road safety investments’.

Elsewhere the government said a recent review of its $1.8m TAC local government grant program had found the program had a positive benefit cost ratio and had improved safety. It said its other local road safety fund (the $210m Safer Local Roads and Streets) would be evaluated in 2027.

Conclusion

Victoria’s goal of halving road deaths by 2030 is not on track and sadly the government’s recent response to the parliamentary inquiry does not give us much cause for renewed optimism.

In addition to its targets on road safety, the current government also has a climate-related pledge to shift 25% of transport trips to active modes by 2030. But Victoria Walks’ analysis of available data indicates that since the Covid-19 pandemic ended, walking and cycling are falling as a proportion of all trips.

It is hard to see these trends reversing without major shifts in road safety and transport strategies and without a major (major!) boost in levels of investment for walking, cycling and public transport.

The 2023-2024 parliamentary inquiry’s terms of reference focused on road user behaviours since Covid-19. This resulted in many recommendations being directed at levers such as education for road users and enforcement of road rules.

Nevertheless, some recommendations focused on our current road environments and whether they protect vulnerable road users from the impacts of human error. This aligns strongly with the Safe System philosophy, which regards human error as inevitable.

There is some acknowledgement that the risks carried by vulnerable road users are a product of long-term planning and investment patterns, which have encouraged Victoria’s growing car-dependency, even for many short trips.

It will take major shifts in policy, planning and investment to halve road deaths by 2030 and make active and public transport attractive, safer options for more people across Melbourne and the state.

We hope to see investment that better protects vulnerable people, and which supports a shift to active and public transport in the May state budget.